BW: So we sampled multiple times, and we brought in a double bass player from Germany who was very experimental in terms of extended techniques, microphone placement, instrument setups, and very experienced. We basically gave him a list of articulations, one-shots, bends, etc., that we wanted him to play and gave him the freedom to interpret them. That's because much of the music in this piece is kind of alien-like that we couldn't notate effectively. We're not great at orchestrating aleatoric music on paper, so it was more like, "Try bending it this way, this is the reference audio."

Q: So, did you also have a score to explain "How to Play" to the double bass player?

BW: Yes, we gave a lot of specific examples of the audio we were looking for. We also provided a lot of texts, like John Cage's writings, that were kind of like explanations of how to play. And during the pandemic, he recorded his playing remotely and sent it back to us. When you put it under the MIDI virtual orchestra, the double bass breathes, and the bow makes really good sound, so it feels like it's alive. There are also textural elements.

Q: And sometimes, unexpected sounds can happen, like mistakes or something?

BW: Exactly! Another big event was that we were initially supposed to record in Vienna, but due to the pandemic and the game's schedule, plans changed and it was canceled.

Q: So, something that could have had an impact on the whole music production was canceled?

BW: Yes.

Q: It's strange to say, but thanks to that, were you able to conduct various experiments in your own studio?

BW: Yes, that's exactly what we did. There were four of us working on the finishing process. We were all in our own studios a lot, and we asked people who could work remotely to do experimental sessions for us. We gathered everything we could play with different instruments such as cello and double bass, and selected only those that might be used. In other words...

Q: Um, wait a minute. You said there were four people, but isn't Finishing Move a duo? But in a video on YouTube, I saw three people on stage with the Apprehension Engine. How many members are in the team actually?

BW: Brian Trifon and I are the team founders. And two team members, J and Alex, who are assistants, are also composing with us full-time.

Q: That's a powerful team, isn't it?

BW: Yes, and also, the so-called standard Apprehension Engine was invented by composer Mark Korven (known for composing the music for the movie Cube). He's known as a horror movie composer (most recently for Netflix's The Witch) and he invented this instrument, came up with the concept and had a luthier (stringed instrument maker) in Canada build it. We commissioned the same luthier for our version, but ours was very expensive and cost around $10,000. It took about 6-8 months to complete, I think. The project team really wanted to do this and was very open to doing strange and experimental things.

Q: In the video of the Apprehension Engine uploaded on YouTube, there is another interesting thing, the reverb sound is distinctive and sounds great. Did you add any plugin reverb or something like that?

BW: Are you talking about the footage of us playing?

Q: Yes.

BW: I don't know exactly how the people who uploaded it to YouTube edited it or what they did, but originally it was from a data patch programmed into a pedal reverb. That particular reverb, what was it called again...?

Q: What was the color and shape like?

BW: It's a dual reverb, which means you can layer two of them together. So you can go from a Hall to a Shimmer, create crazy pitches, or shift the line to something else using pitch shift. When I get home, I'll message you the exact panel. Basically, it's a combination of several signals. (A later message from him said it was a Ventris Reverb from Source Audio.) I'm not really fond of the sound of spring reverb. I prefer the type of sound that has a more complex resonance, so I don't use spring reverb that is immediately recognizable as such.

BW: Much of our sound is heavily processed with things like reverb, distortion, delay, EQ, and so on. It's not necessarily something that's incredibly interesting or ear-piercing, and in fact, even the louder sounds aren't that big. The apprehension engine uses a piezo pickup and we connect that through guitar pedals to create more interesting sounds. That's what we usually do. Alternatively, we also record the Apprehension Engine with a microphone and process them using a lot of plugins on the computer.

Q: I see, that's very interesting. It seems like a tremendous amount of terrifying sounds were created that way, but they are basically sound effects, right? However, in The Callisto Protocol, it seems like music also functions to achieve a similar texture and effect as those sound effects. How does the team differentiate between the two?

BW: Actually, Glenn, who is the studio head, didn't want us to make a distinction between "is this music or sound design?" It was more like giving us the freedom to "design non-musical music." It's music that doesn't sound like music and pushes the boundaries of "is this music?" Apart from cutscenes, there isn't much consonant harmony material. So it's about what sound design is and what we really wanted to do in music. For example, when you're experiencing some unusual exploration, you might hear something around the corner. At that moment, we wanted to create a feeling of uncertainty, like "Huh? Is that creature-like sound coming from behind or around the corner a part of the sound of the space I'm in, or is it music?"

BW: The impact and emotions that it gives to the player, regardless of whether the sound is music or sound effect, is very important. What Glenn has always been saying is that when a cue is made, "No, this sounds too much like music." So his feedback was not like what composers usually receive, such as "This sound has too many notes." It was very experimental. In horror, people are looking for those otherworldly things. In music, horror is one of the few genres where sound design can push its limits.

BW: So, in this game, you won't be able to distinguish between music and sound effects. It's like this - you're living in a world where you're just feeling scared. The protagonist isn't a superhero. They don't have any superpowers. They're just someone who's in really bad circumstances. And they're just trying to survive. Trying to prove that they exist. They've been put in prison. They're thinking, "How did I end up like this?" Suddenly, they're in this situation and they're feeling anxious and desperate. We want to make the players feel suffocated and anxious. This game isn't a fun "Campy Horror" game, so be aware.

Q: So, how much time did it actually take for the real-life performance and editing? And I assume you had to try and learn a lot to create good sound using this complex Apprehension engine, so it must have taken a considerable amount of time, right?

BW: This is something we do for all projects, but we like to do the toolkit work upfront. That means we imagine what projects we'll be working on in the future. We create custom sound libraries, custom instrument libraries, like Kontakt instruments or UVI Falcon instruments, and make a lot of fully designed sources that we can quickly pull out when making cues. So, it's like concept art where we do a lot of work upfront and get ideas. We don't know exactly how we'll use it, but we prepare for a custom music sound library for the project. So instead of pulling from existing commercial libraries, we made custom sounds for the IP (Intellectual Property) ourselves. It's common in games, and we always do it, but sometimes something goes online very late, and we need to finish it quickly. Especially for cinematic ones. So, we do a lot of R&D (Research and Development) and make a lot of content and materials to work with, so we can combine them and work more quickly. It's like doing prep work for cooking at the beginning of the week, so you can just cook the food with fire for the rest of the week, right? That's how it is.

Q: I see. If The Callisto Protocol were a dish, it would be very difficult to choose the ingredients. It seems like it could result in a somewhat grotesque dish. (laughs)

BW: Hahaha! Yeah, that's right. Anyway, I've spent a lot of time just experimenting. Takahiro, you've probably done a tremendous amount of sound experiments too, right? Some of them you just have to throw away because they're terrible. That's why you need time to play. Not all sounds you come up with on a whim will sound cool, and not all sounds from an instrument you don't know how to play will sound cool either. So, you just have to play around, record a lot, process it, and you need to give and take even more. For example, let's say you just sit down and write an orchestral piece. This is the template and this is the melody. You already know that, right? Well, what if you do this? What if you try that? Oh, but what if you process it this way? Oh, this is really cool, and that's how you come up with experimental and wild sounds. You might even forget what you were originally thinking and just want to do cool things.

Q: I see, it's a really passionate story. By the way, I think there was experimental electronic music in your early career background, does that lead to that challenging attitude?

Q: Trifonic (a separate project from Finishing Move that releases original electronic music) - you know about them, right? They are deeply influenced by sound design, custom-made sound tweaking through sampling, and other sound design techniques. We are not classically trained musicians, so our values and spirit are more like those of electronic musicians who can pull from various sources instead of saying, "this is the orchestra, and this is our instrument."

Q: I see. Even guitarists these days experiment with plugins or other methods to create memorable sounds. Can you tell me about the interactive music in The Callisto Protocol?

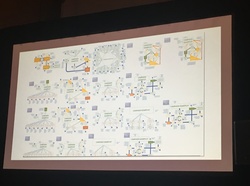

BW: We tried various approaches for that as well. Interestingly, what we thought would work well ended up changing as we played and experienced the game. One of the concepts for combat was to use very heavy sounds like blocks or percussion. We made some mockups, and they were cool and well-received. Then, sound design was added, including bones, blood, and crushing, and five enemies attacked simultaneously. The cues, which were initially heavy, became too heavy because too much was happening. So we temporarily put the intense combat on hold.

BW: Then we came up with a system based on very introspective drone sounds. We incorporated a few elements with high tension and gradually increased the sense of tension. We also avoided too many overly floaty and passive sound effects that would fill up the entire soundscape, so it wouldn't become overwhelming. We wanted to express fear and give the audience a strong sense of unease. We used a lot of Shepard Tone, which is a sound technique that creates the illusion of constantly rising sound.

Q: Did you use Shepard Tone subliminally?

BW: Yes, that's right. We created the sounds using very slow movements at a very small level. We made a lot of custom chapters for Shepard Tone. We created a script in UVI Falcon that would essentially make any material sound like a Shepard Tone. We then modified the script to make it more realistic.

Q: So, did you create the samples from scratch to load them for Shepard Tone, using UVI Falcon?

A: Yes, that's right. We used a variety of materials as samples, not just high-pitched strings with high tension. We captured the samples and loaded them into Falcon to create Shepard Tone from there.

Q: That's really interesting! It reminds me of using granular synthesis with Omnisphere to do similar things.

A: I've tried various things with granular synthesis too. It's really interesting.

Q: Moving on to the next question, the sound that impressed me the most in The Callisto Protocol was actually the soundtrack. It's very different from typical movie sounds or other soundtracks that mimic electronic music. It features deep, complex reverbs and sounds that sometimes cross from left to right, as well as impactful hits and piercing stingers that are so great that I've never heard them before. How were these sounds created? Are they different from the sounds in the game, or were they made using the sounds in the game?

BW: Actually, almost all of it is made up of in-game materials, but we arranged it quite skillfully. In other words, you could say that we re-recorded almost everything. I wrote four hours of music for the game, but I couldn't include it all in the soundtrack. A soundtrack that's too long isn't desirable, and I felt that way myself. I wanted to provide a concise experience that wouldn't become monotonous. We didn't need a soundtrack that lasted six minutes with drone music. So we arranged it linearly, just like the in-game experience, and compiled it into a best-of the in-game music. We wanted listeners to feel like they were progressing through the game, and above all, we didn't want to bore them. We focused on the sonic elements of cinematic moments, tension, fear, and anxiety, and created an 80-minute experience from a 10-hour game. In other words, we edited and reconstructed the music. We composed 24 tracks from hundreds of music materials, but each track is sometimes composed of four to five, or even six, different cues from the game. We also wrote transitions to connect them. Instead of including all the tracks from the game in the soundtrack, we selected the tracks that we liked and were suitable for the showcase, and constructed them to provide a tighter experience. The soundtrack is our perfect opportunity to express ourselves with music.

Q: Was the orchestral sound recorded live, or was a library used?

BW: It's a combination of solo performances that we played ourselves or had others play, and Kontakt. We didn't have 80 people in the room. Unfortunately, due to pandemic-related cancellations, we couldn't have the full orchestral recording session we wanted. So for the larger ensembles, we used Kontakt in addition to individual instrument performances. And we thought of ways to combine the terrifying Apprehension Engine sound with the orchestra using some hooks. I don't think it would be possible to do that with live performance. Because we're reconstructing many cues for the soundtrack, it's almost impossible to record them while trying out combinations by researching the asset history. And it was much more reasonable to have a lot of control at our fingertips. I've done recordings with large orchestras before, but there were so many unpredictable elements.

Q: Who was responsible for the mixing itself?

BW: We always deliver a fully mixed product in our projects, I have a background as a professional mix engineer, so I handle that for the team. For The Callisto Protocol, we provided quad assets and I was responsible for some of the early implementation work in Wwise and Unreal, however, due to the scheduling, I had to step back from implementation and pass that off to Striking Distance Studios. Generally speaking, we handle implementation around 25% of the time (using Wwise and Unreal) and the remaining 75% of projects we send completed mix assets or stems to the game studio to do the implementation.

Thank you Brian!